If we choose to face reality, we know that teen sexting has become a normative part of adolescent culture. Of course, not all adolescents are doing it, but many are sexting. What we learned from the years of the “JUST SAY NO” campaign and more years of research is that preaching abstinence just doesn’t work. If we want to protect children from the darker side of sexting, we need to educate and inform them about the practice, so they can make their own, hopefully well thought out, decisions.

What are the tenants of Safe Sexting?

- You are responsible for your own safety.

- Know the risk

- Know how to protect yourself

You are responsible for your own safety

The digital world can be a risky place. Aware parents will have talked to their children about online sexual activity and perhaps filtered or monitored devices such as phones or laptops. However, no filter or monitor can truly protect a child from the risks of online sexual behavior. Ultimately, your child is responsible for his or her own behavior online. What they do or do not post, text, snap, etc. is their own responsibility.

To help your child be more proactive about their online safety, here are some things to think about and talk to them about. Before you send a picture or post, stop and count to ten. Ask yourself these questions:

- Do I really want to send this picture or video?

- Do I feel pressured to take or send this image?

- Do I trust that the person I send this to will never share this image without my consent?

It is very true that many children, particularly girls, feel a great deal of pressure to participate in taking and sending sexual images. There are also online predators who will groom, intimidate or threaten a young person to convince them to take pictures. In these instances, there is no consent. Coercion is never consent.

If your child chooses to engage in consensual sexting with a peer, they should truly want to take the image without feeling any pressure to do so. They should also trust that, no matter what, the person they send the image to will not share the image. If all of these parameters are met, then the sexting is consensual and if your child takes and sends an image, they are assuming responsibility for their actions.

Know the Risk

Even in the case of consensual teen sexting there is a lot of risk. In order to engage in safe sexting, the person doing it (adult or minor) needs to know the risk involved with the behavior. So what are the risks?

Sexting as a minor may be illegal. Every state has a different law regarding minors producing and sending illicit or sexual images. The punishments for the behavior also vary from state to state. In some cases, a child can be the producer and distributor of child pornography as well as the victim of the same crime. Some states have decriminalized consensual sexting between two minors. Know the law in your state and share that with your child.

Another risk is that someone you do not want to see your image may see your sexual image. This is non-consensual sexting. You may have sent a sexual image to someone with whom you are in a relationship. This may have been consensual at the time. Then, something goes wrong in the relationship, and you are not together. Revenge porn is a real thing. If the person you were dating changes their feelings or gets mad, they have an image that they can send out to every other person in high school or post to a revenge pornography site. Anytime you send a sexual image there is always a risk that someone you do not want to see it will see it. It is also possible that many, many people may see the image.

Protect Yourself

In this arena of uncertainty, where something can go viral in the blink of an eye, how do you protect yourself? Here are some guidelines to help your child protect themselves.

If you choose to consensually share a sexual image with someone, only send an image or video that you would not mind someone else seeing. Are you ok with just anyone seeing you nude or engaged in a sexual act with someone? If you are not okay with that, and choose to send an image, perhaps send a picture in a bathing suit or underwear. I don’t want this to be read as advocating for teens sexting but for those who choose to do so, to send an image that the sender would not mind any and all to see.

If you choose to send a sexual image, only send an image to someone you trust. Sending an image is a great act of trust as you lose control of that image the moment it is sent. You need to truly and completely trust that the person you send it to won’t someday get mad at you and send it to all of his or her friends or post it online without your consent.

How do you know who you can trust? To answer this, I will borrow from Brene Brown’s concept Anatomy of Trust otherwise known as BRAVING. This can be applied to you or another.

- Boundaries – The person you may send this image to always respects your boundaries

- Accountability – The person you may send this image to always owns their mistakes, apologizes and makes amends

- Integrity – The person you may send this image to always acts with integrity, does what is right instead of what is easy or fun.

- Reliability – The person you may send this image to is reliable. They always mean what they say and say what they do.

- Vault- The person you may send an image to NEVER shares things that are not his or hers to share. They don’t gossip and they keep confidences.

- Non-Judgment- The person you may send this to will not judge you.

- Generosity- The person you may send this image to will assume the most generous thoughts about your actions and intentions.

If the person you are thinking about sending a sexual image to does not meet the core pieces of the anatomy of trust, you may wish to rethink sending him or her a sexual image.

To conclude, I would like to reiterate that my intention here is not to encourage or glamorize the practice of sexting among adolescents. My point is to be realistic. If teens are going to engage in sexting we need to empower them with accurate information and guidance about how to do so safely. Talking to your child about Safe Sexting arms them with information to make their own informed decisions.

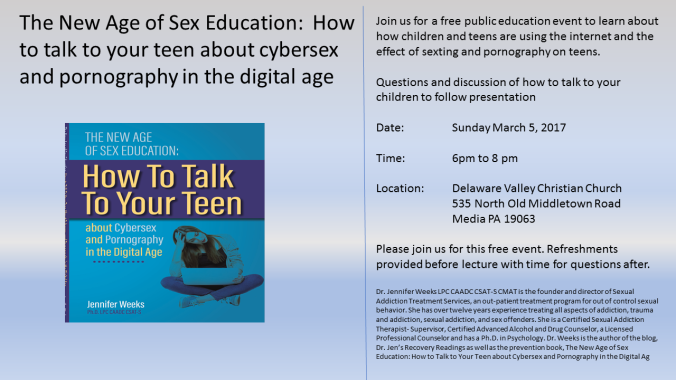

For more information on how to talk to your child please see my book, The New Age of Sex Education: how to talk to your teen about cybersex and pornography in the digital age.

For more information on Dr. Weeks, Please see our website www.sexualaddictiontreatmentservices.com

Join me this Friday for a free one hour webinar hosted by The Center for Healthy Sex at 12:00 pm (PT) to talk about the effects of cybersex and sexting on children.

Join me this Friday for a free one hour webinar hosted by The Center for Healthy Sex at 12:00 pm (PT) to talk about the effects of cybersex and sexting on children.